Brakes have evolved, but not every fleet uses the right friction

Tractor-trailers don’t stop on a dime. You can blame the realities of physics for that. But a standard 6×4 tractor traveling at highway speeds still needs to stop within 250 feet, which is dramatically less than the 355 feet allowed as recently as a decade ago.

The reduced stopping distance (RSD) brakes that make this possible were no small feat of engineering. Meeting the shorter limits meant higher brake torques on steer axles. Front brake spiders became heavier, mounting bolts larger, and 16.5-inch brakes more popular. Then there were changes to the secret ingredients used to create the friction material itself.

It was all for a good reason. The U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated the change would save 227 lives, 300 serious injuries, and US $169 million in property damage per year – once all heavy tractors were equipped with the enhanced stopping systems.

But the rules don’t apply to all the brakes on the road today. Not even close.

While the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS 121) and its Canadian counterpart apply to brand new tractors, it’s a different story in the aftermarket. Once the trucks are in service, there are few limits on the friction material that can be used.

It’s still possible to buy friction material that doesn’t meet the RSD requirements, says Frank Gilboy, Bendix Vehicle System’s product director – foundation drum brakes and actuators. The offerings continue to support legacy vehicles and configurations that were not affected by the change.

“The legislation does not mandate like-for-like replacement, so there’s a ton of aftermarket stuff,” adds Meritor senior product manager Eric Coffman. “You’re going to have a value product, maybe a mid-grade product, and RSD production-level product,” he says. “It’s a trade-off of performance, wear and cost.”

If the brake shoe fits, you can wear it.

Performance differences

The value-priced material can admittedly be a perfect fit in some applications. Consider a truck that leaves a job site or farm just once every few months. Such brakes are not going to wear down anytime soon.

“It doesn’t have to be 23K friction all the time,” Coffman says. “It’s matching and kind of choosing a quality level to match your application.”

Still, there’s a case to be made for using high-quality friction material when it comes time for most brake jobs. The brakes are designed as a system. Change just one piece of that system, and the performance can degrade.

Thousands of hours are invested into the design and balance of braking systems to ensure the right amount of friction, Gilboy explains. And it’s about more than wear alone. It’s also a matter of addressing noise and vibration. “Keeping it OE guarantees you aren’t upsetting that system.”

Collision mitigation systems, especially rollover stability systems, are designed with the shorter stopping distances in mind, adds Richard Beyer, Bendix vice-president – technical sales and vehicle systems.

It all means that maintenance teams should pay close attention to spec’ sheets and the markings on different products, rather than focusing on price alone.

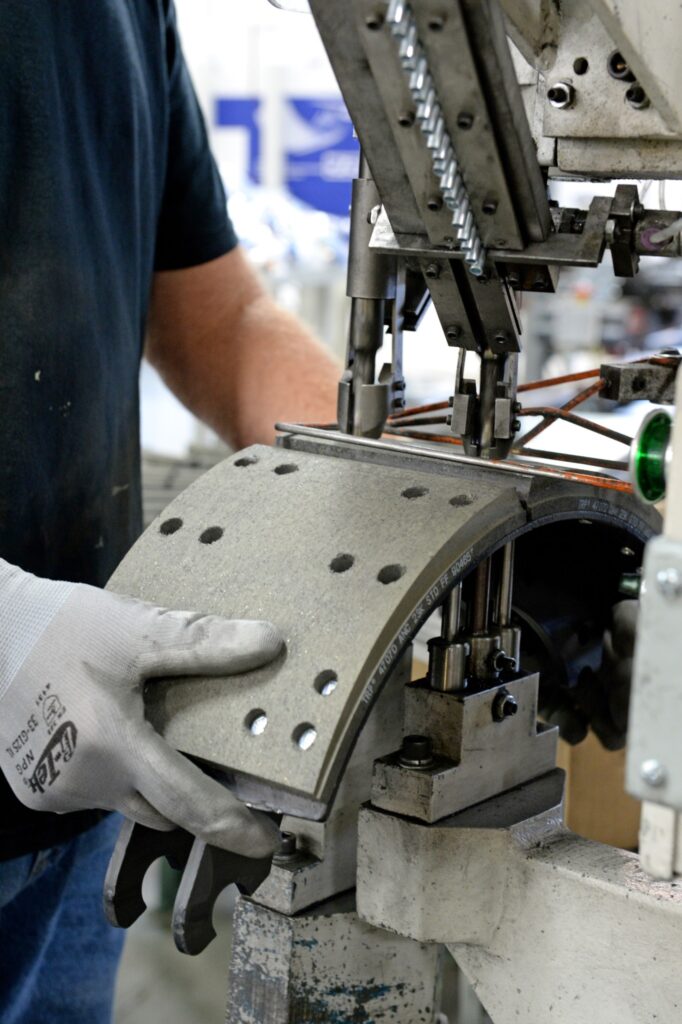

Look at the edge of the brake friction material and there will be markings to identify the brand, formula, part number and related code. Bendix even applies a sticker to a brake shoe’s web to indicate when it complies with RSD standards. But keep in mind that the markings are also unique to specific product lines. The “FF” on one product might not mean the same when applied to the offering from another brand.

Sometimes there may be a need to dig a little deeper into various product claims, too. A reference to passing an FMVSS 121 test on a dyno, for example, may not be the final word about how well the brakes are designed to perform. Read the fine print and you might find that the tests were limited to cold brakes. In contrast, OE-level friction material is designed to work in every environment.

“You’re not just trying to check one box,” Beyer says.

Fuel economy and brakes

Even vehicle changes in the name of fuel economy can represent new challenges for some friction material. Extra fairings have been known to reduce the all-important flow of air around the brakes, Beyer explains. “Heat is a big deal. The hotter a brake runs, the faster it’s going to wear.”

In contrast, disc brakes tend to run cooler in such situations because of the rotating disc’s pumping action. “It has a positive effect of pulling air through it,” he says.

One of the best ways to control brake temperatures is to opt for heavier drums, Coffman says, noting that cutting costs on these components can lead to premature wear.

“Downspeeding introduces challenges of its own,” Beyer adds, noting how a move from 1,400 to 800 rpm will drastically change the performance of a compression brake. And less compression braking leaves foundation brakes to shoulder more of the stopping power.

Premature wear

At this point, it all comes down to a question of whether the friction material is performing as promised.

Signs of problems with friction material can emerge several ways. Mechanics might spot an excessive amount of brake dust or material that is beginning to glaze over and tear into the drum. Drivers might complain about added noise or vibration. Or maybe they’ll report increasing stopping distances.

“When you insert another friction into that [vehicle], it’s a bit of an unknown,” Gilboy says. “The brake will tell you that.”

And the challenges with premature wear are not limited to the surface that contacts the drum. Any rust that builds between a brake shoe table and lining block can ultimately push a lining outward, causing it to buckle between the rivet heads and crack across the lining.

“Rust jacking is absolutely an issue,” Coffman says, referring to the process.

De-icing compounds are largely to blame for the situation in Canadian operations, but they aren’t the only cause of the issue. He refers to one concrete fleet in the southwestern U.S. that was plagued by rust jacking which was ultimately linked to the acid wash used to clean the trucks.

It’s another way premium products can make a difference. Higher-quality brake shoes are powder-coated with epoxy or urethane resins.

Fastener choices make a difference in the fight against corrosion, too. Steel parts should be attached with plated steel bolts and nuts.

And remember: the cost of premature wear is not limited to the products alone.

“Every time you’re doing a brake job, that’s an asset that’s not rolling,” Coffman says. It sounds obvious enough, but the shift to a premium product might eliminate one of those brake jobs a year. As the saying goes, your mileage will vary, but the longer replacement timelines could help to better align the work with broader duty cycles and other maintenance issues.

When it comes time to change the friction material, it should also be replaced across an entire axle. Focusing on a single wheel end could affect the brake balance, Beyer stresses.

Environmental gains

In the midst of all the performance-related updates, other changes have come in the name of environmental gains.

Friction material includes five components, Coffman explains. There’s a structural package to hold things together, fillers, binders, and friction modifiers that are lubricants or abrasives. The friction material itself can include a couple of dozen ingredients that are tweaked and modified in the name of performance.

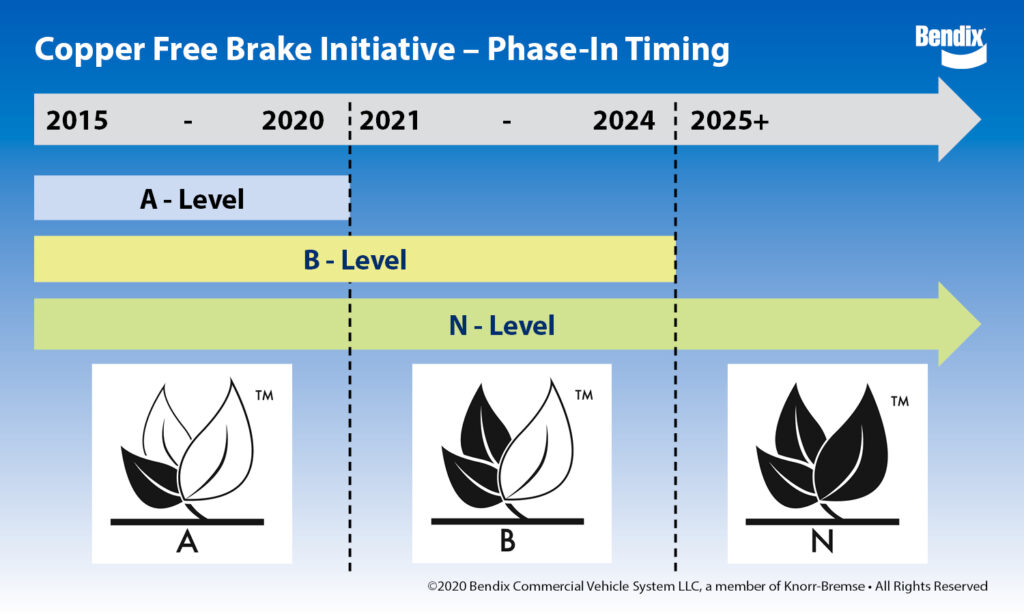

Washington and California laws first established in 2010 now limit the formulas to 5% copper by weight, and by 2025 California will slash that limit to 0.5%. Those changes came after researchers found that brakes accounted for 35-60% of the copper found in the runoff flowing across California’s urban watershed.

The copper served a purpose. It effectively transfers heat and helps the brakes perform in cold weather, preventing unwanted squeaks along the way, according to the Copper Development Association. But it is fading away – much like the asbestos that was embraced until the mid-1980s because it tolerated heat and mitigated noise. Concerns about the material causing asbestosis put an end to that.

“There was no ‘silver bullet’ copper replacement. There was more of a change in the cocktail,” Coffman says.

And the cocktails continue to evolve.

Have your say

This is a moderated forum. Comments will no longer be published unless they are accompanied by a first and last name and a verifiable email address. (Today's Trucking will not publish or share the email address.) Profane language and content deemed to be libelous, racist, or threatening in nature will not be published under any circumstances.