Hendrickson’s ZMD delivers a shockingly smooth ride — without shocks

TORONTO, Ont. — When was the last time you heard a driver say something positive about a trailer suspension? Most drivers would barely be aware that their trailers even had suspensions, but a design innovation from Hendrickson has actually prompted drivers to call the company asking what type of suspension they were pulling. They wanted to urge their bosses to spec’ the same suspension on future trailer orders.

That innovation, called Zero Maintenance Damping, began life about 10 years ago and was originally conceived as a maintenance saving idea. It first appeared on the Ultraa-K suspensions in 2014, where it’s now standard. It’s also available currently on select Vantraax and Intraax systems.

“There are about 150,000 Ultraa-K suspensions in service now and nearly a million ZMD air springs out there,” says Scott Fulton, director of product development at Hendrickson Trailer Commercial Vehicle Systems. “We really expected it to be just an improvement to the lifecycle cost of an air suspension, but the volumes of positive feedback we have received suggest it’s much more than that.”

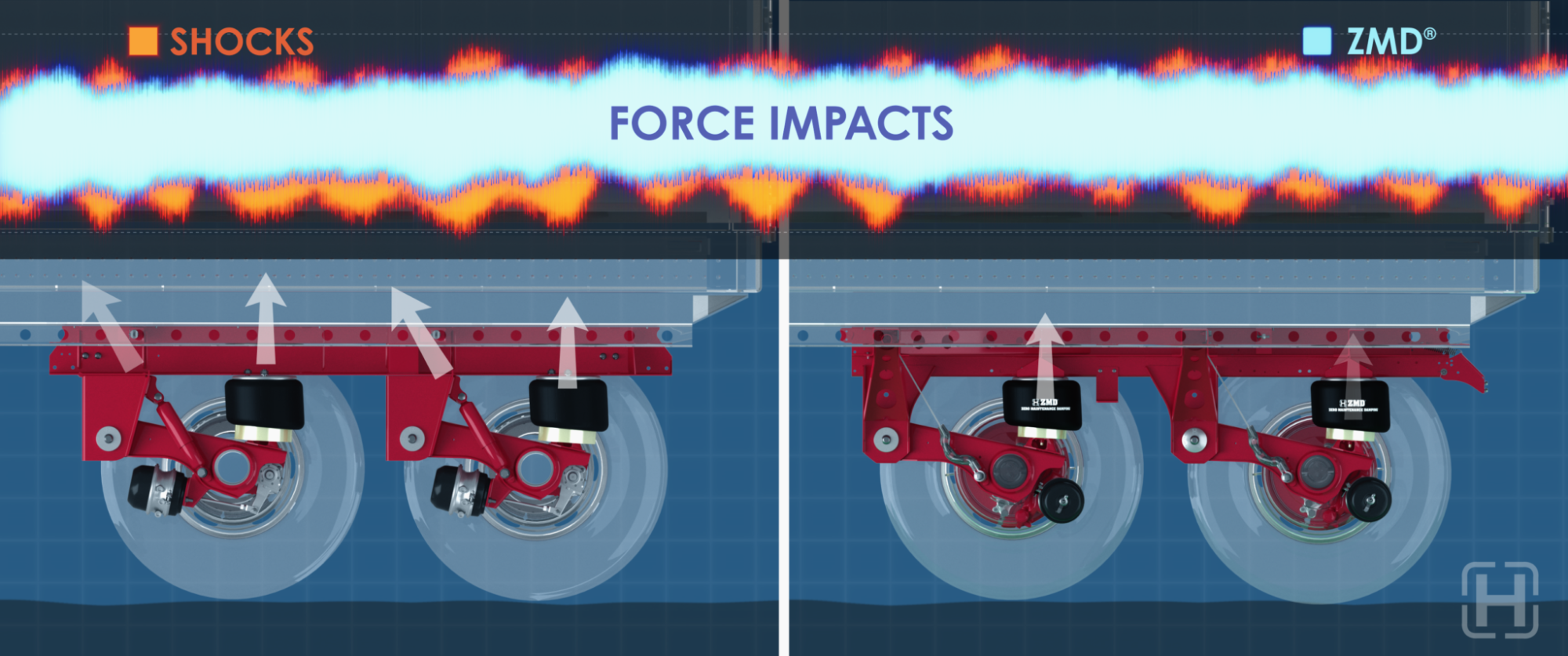

Fulton says they didn’t understand what was going on at first, so they took a few trailers, instrumented them up, and began studying what was going on. “We soon found that the ZMD suspension system reduced certain forces that are transmitted to the trailer and that it did improve the ride in ways we could document and understand.”

How the ZMD works

The design intent with what became ZMD was to reduce the total lifecycle cost of air suspensions. They looked at various components and their life expectancy and decided the shock absorbers had to go. But shock absorbers provide the necessary damping in an air ride suspension.

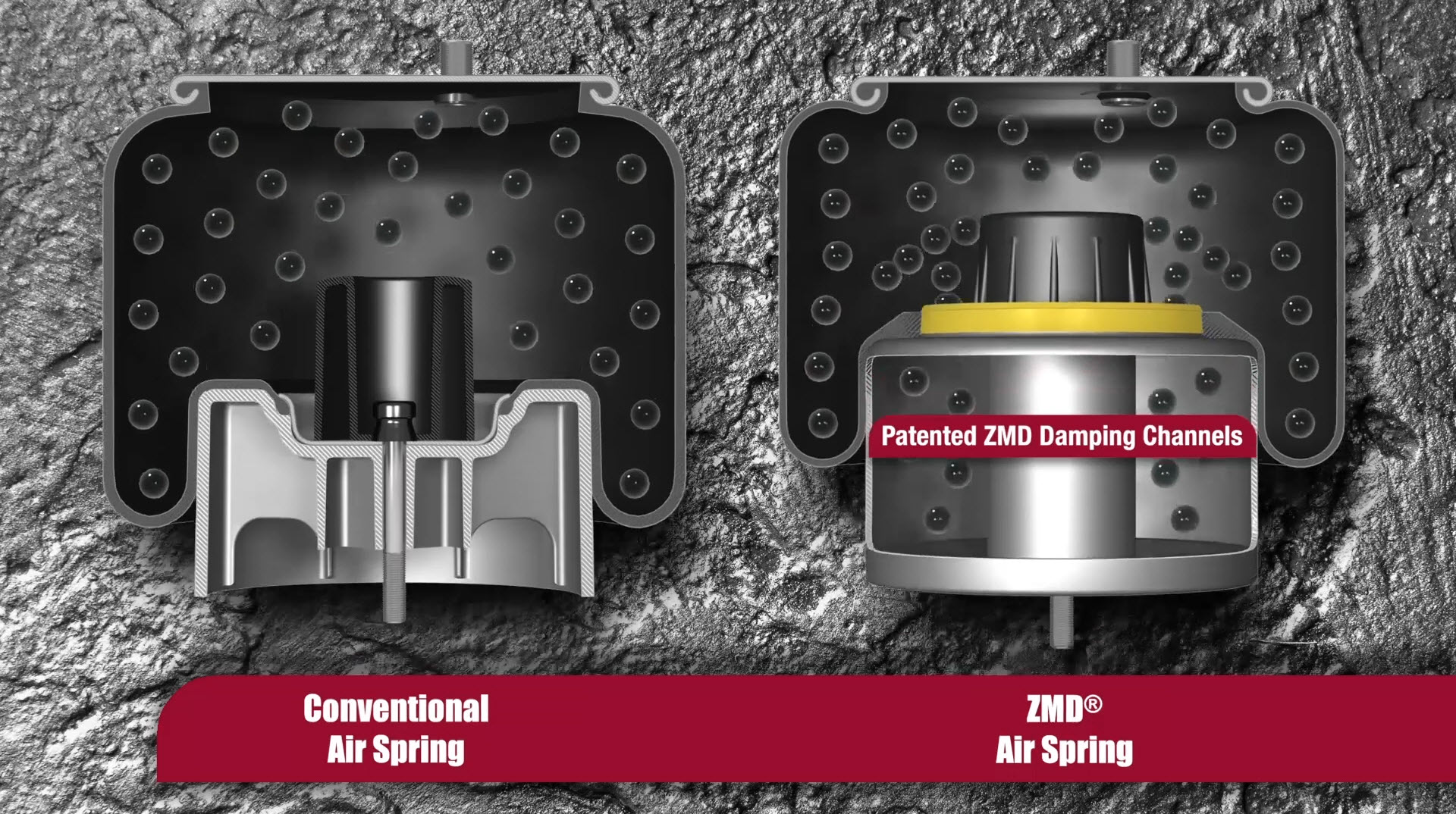

All suspensions require some form of damping, which resists the motion of the suspension and the trailer. In a leaf-spring pack, for example, the friction between the spring leaves provides the damping force. Since an air spring has no internal resistance, some damping mechanism is needed. Hendrickson was able to eliminate traditional shock absorbers by designing a new air spring and piston assembly.

Essentially, the air bag and the piston form a single sealed air chamber separated by a several tiny air passages between the bellows and the piston. As the air spring is compressed by the road inputs, air is forced from the cavity inside the air bag into the cavity inside the piston. The resistance of the air moving through the passages between the two air chambers and the associated increase in pressure provides the damping force formerly delivered by shock absorbers. There are no more moving parts.

“Testing showed this design was absolutely as effective as a hydraulic shock absorber but it came with some unique and unanticipated side effects,” Fulton says. “It improves the ride quality of the overall truck/trailer combination for reasons that we came to understand only after we launched the product.”

The big difference between a spring and an air suspension is that the air suspension adapts to the load you’re carrying. More weight requires more pressure in the system as controlled by the height control valve. What doesn’t adjust is the shock absorber. It’s designed for the heaviest load that trailer is ever going to carry. With the ZMD, because the air is doing the damping, the damping rate also adjusts with the payload.

Where you see the real benefit is on trailers with diminishing loads or lightly loaded trailers, because the damping rate is adjusted down along with the load the trailer is carrying.

Fulton says shock absorbers are non-uniform in the way they perform damping. It collapses easily when hitting a bump and does all of its work as it extends back to its resting position, allowing the suspension to return to its ride height.

“That’s how it takes the energy out of the system,” he says. “The drawback is when hitting constant bumps. The shocks compress and the wheels can come off the road. With ZMD, we can damp in both directions.”

There’s yet another benefit: diminished fore and aft forces transmitted to the trailer. With the shock absorbers positioned as they usually are, roughly 45 degrees from horizontal between the trailing arm of the suspension and the body of the trailer, the shock loads experienced by the trailing arm are transmitted to the trailer as a force that results in what drivers feel as a punch to the kidneys.

“We have changed the direction of the force going into the trailer from slightly forward to vertical, and we can adjust that force based on the payload,” says Fulton. “The drivers get a more comfortable ride and there’s additional protection for the cargo and trailer structure from road inputs, which helps extend the life of the trailer.”

Driving Ultraa-K with ZMD

I was initially a bit skeptical about the bold claims Hendrickson was making regarding the improvements in the ride with ZMD. After a pre-ride briefing with Fulton, I understood the principles behind ZMD — forcing air through tiny openings to resist movement in lieu of mechanical shock absorbers. I understood that removing a source of forward-vectored shock loads from the van undercarriage might improve the driving experience, and I could clearly see how ditching the shocks would save a few maintenance dollars, but I honestly wasn’t prepared for the scale of the improvement in the ride.

I drove two trailers on three loops around a test course through the Canton, Ohio area. The first was an empty van trailer equipped with a steel spring suspension. The second run was with an empty van equipped with an Ultraa-K suspension and ZMD technology. The third run was the same trailer with about 10,000 pounds of dunnage placed directly over the rear bogies. I used the same air-ride Volvo VNR for all three loops.

The empty steel-spring trailer was predictably nasty. The road leading from Hendrickson’s gate to the freeway access was really nothing more than a loose grouping of pot-hole patches that shook one of my video cameras right off its dashboard mount. Out on the freeway, the concrete washboard continued beating on the truck, which each trip over a seam resulting in a slap in the back. While passing over a series of bridge joints at a modest speed, I could distinctly feel the three sets of axles passing over the joints, starting with the steer — thump, then thump-thump as the drives went over, and after a pause, thump-thump as the trailer axles went over the seams.

There were three sets of railroad track on the route. The first two weren’t too bad, the third was brutal, with four sets of tracks, each grade crossing badly deteriorated. That one was enough to bounce the trailer axles right off the ground at just 40 km/h.

The second loop around the track with the empty ZMD trailer felt about 500% better. I could still feel the potholes on the first part of the route, but they were considerably tamed by the trailer suspension. The bumps were still noticeable, but the aftershocks were gone. The washboard freeway was still bumpy, but again, I felt just the bumps as the tractor axles crossed the slabs. That jolt from the rear that I felt with the steel-spring trailer was greatly reduced. The bridge seams were barely noticeable as the trailer axles passed over.

And that nasty set of tracks still nearly knocked me out of the seat as the tractor went over, but the trailer just kind of reminded me that we had just crossed over a rough set of tracks.

When we returned to Hendrickson, the crew placed a 10,000-pound test load in the back of the trailer, right over the bogey, and away we went for round three. To avoid the repetition, I’ll simply say that I could no longer any input from the trailer. The bumps were just from the steer and drive axles.

Traveling over the bridge seams, I felt the thump and thump-thump as the tractor went over, but I could not feel anything from the trailer. Seriously. The nasty tracks half-way around the route were also a non-event. I didn’t see the wheels come off the ground and I could barely feel the trailer axles cross the tracks. There’s was just the faintest thump from the back and absolutely no jolt to the kidneys to be felt at all.

Driving along the freeway at highway speed and hitting the usual assortment of bumps was just like going over the bridge seams. I felt the tractor wheels go over the bumps, but not the trailer wheels. It was literally as if the trailer was riding on air.

Now I understand what prompted those early-adopter drivers to call Hendrickson. This suspension was quite unlike any trailer suspension I have ever driven before.

The real beauty of this design is that there are no moving parts, nothing to wear out over time. The air springs themselves will likely last as long as any air spring would, so five to 10 years with regular inspections. If something were to fail, or if the air passages were to become obstructed the worst-case would be the same situation as a trailer with a non-functioning shock absorber. “You’d lose the damping action, but that’s it,” Fulton says.

A design change that would have saved a fleets a few hundred dollars over the typical life of a trailer air suspension could be driver recruiting and retention tool worth far more than the time and the cost of replacing a few worn out shock absorbers.